By Bob Confer

I write about nature in Allegany County and spend many a weekend here, but my real home is in Niagara County, in a place called Gasport, which is located along the Erie Canal.

The Erie Canal towpath (now known as the Canalway Trail) was once the interstate for itinerant workers (hoboes) who traveled from town to town in search of their next farming or handyman gig. While doing so, they frequently stopped at my family’s farm, which butts up to the canal. It was an attractive spot to set up camp because of the fresh water they could drink from a brook that runs through our woods, the same brook from which they ignited gas that bubbles from it for cooking their dinner (there is a reason it’s called GASport).

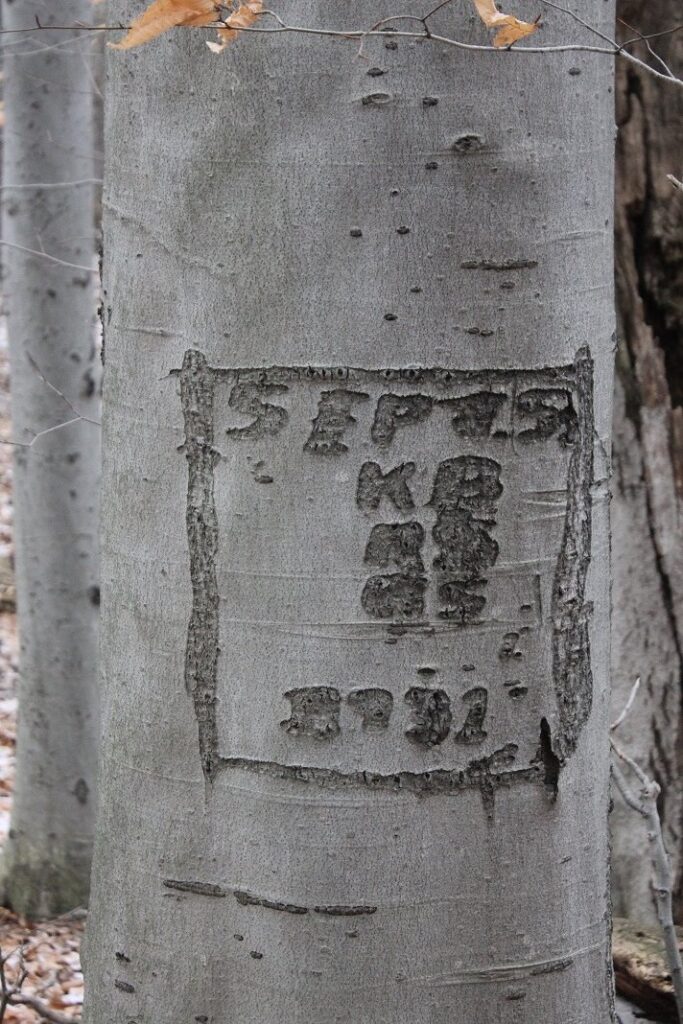

While there, they often killed time by carving their names and other things in the bark of the beech trees that were quite common in the woods. The smooth gray bark, so easy to cut with a pocketknife, has always been quite inviting to amateur artisans, not to mention young lovers who wanted their names forever inscribed in Mother Nature for all the world to see. The hoboes, the lovers, and anyone else interested in making a statement left their calling cards on the beeches — old-fashioned graffiti that remains to this day.

Those trees tell stories. On the trees that were cut when they were mature and thus slower to grow, I can still make out dates from the early 1930s. Some of the handiwork, less legible as the tree grew, obviously came from much earlier times and younger trees. There are names; some of them belonged to the hoboes, while others I recognize as locals who probably carved the tree when they were in their teens and 20s. Now, they are in their senior years and their arboreal artwork has aged less dramatically than they.

One of those beeches has neatly cut into its bark two words: “Ray Confer.” My grandfather did that when he purchased the farm in 1955 when he was fifteen years younger than I am now. He has since passed, so that tree has always offered a comforting portal to a time gone by.

Sadly, these trees – all of them – will quite soon, no longer be able to tell their stories. In the early 2000s, beech bark disease reared its ugly head on the Niagara Frontier in volume and then spread across Western New York, bringing with it its deadly one-two punch. First, an insect attacks the bark. Then, the wounds left by the insects are infiltrated by a fungus. It doesn’t take long for the once-beautiful bark to crack then fracture completely, falling off the tree. The malnourished beech topples over within a couple of years of its first symptoms.

The disease is taking a toll on local forests, wiping out what was one of our most abundant trees and our best storyteller. It’s disheartening to think that the trees that should have outlived me won’t, taking with them the interesting connection I have to my family and the hardworking men who made their way across the region in hopes of overcoming the economic realities of their time.

You can also find similar destruction and similar history throughout Allegany County. Before the disease totally guts local forests and hedgerows, look for carved beech trees. One hotspot is along the WAG Trail – hoboes walked along the Wellsville, Addison, and Galeton rail line and its predecessor that was part of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad as it, much like the canal path near my home, provided easy access to rich farmland in which to secure a job. Also, if you can hike some private land, look for older beech trees in the high country of Alma and Bolivar where oil fields were once abundant. Workers who tended to the harvest of crude carved their names and loves in trees near the wells, pumps and access roads.

Appreciate that artistry while you can. Bet yet, capture it. Not one to let memories – history! — die so pitifully, over the past few years I’ve been taking photographs of the various trees and their carvings that remain. By capturing the images on film we can maintain the carvings for the ages, just as their artists had intended.