The Ringed-Neck Pheasant has become a rare sight in WNY due to several realities

By Bob Confer, photo by Craig Braack

If you are a Baby Boomer, you will remember how extraordinary pheasant hunting was from the mid-1950s into the early-1970s. It was one of the most popular outdoor pursuits in Western New York, far rivaling the buck fever you see nowadays when deer season opens.

The shoulders of rural roadways were full of parked cars while factories and classrooms would be empty as families shared Opening Day out in the field. Pheasants were everywhere and in huge numbers; hunters had much success and put many a savory bird on the dinner table. At the peak of the pheasant hunt, New York hunters would harvest a half million ring-necks per year.

That era seems so long ago and almost unbelievable, even mythical, to today’s hunters. Except for small, periodic releases on state lands, ring-necked pheasants could be considered rare in WNY. In places where pheasants were once taken for granted and maybe even considered bothersome (there were so many they’d get caught in farm equipment at harvest time) seeing or hearing one is now a “wow!” moment.

How did we go from feast to famine in just a half-century?

There are four big reasons why the pheasant population has dropped by more than 95% percent since 1970:

Loss of habitat

In explaining why we are seeing bears, beavers, bobcats, flying squirrels, fishers, and more all across WNY, my recurring answer has been the changing landscape. The same factors that have contributed to their arrivals – the loss of family farms and the transformation of fields to forests – have also led to the demise of the pheasant.

Where once stood vast pastures and grasslands for cattle to graze or hay fields to keep them fed through the winter months, wooded areas now exist. Pheasants are not woodland birds and need wide open spaces and tall grasses to feed and also to raise young.

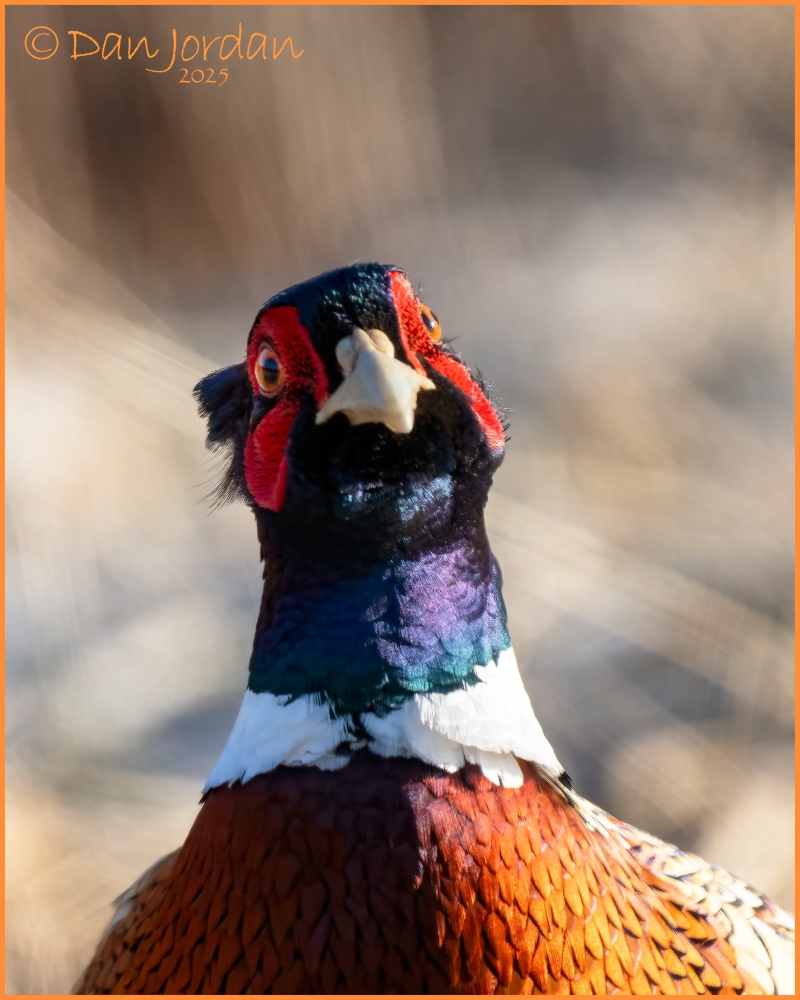

Photos of the iconic male Ringed-Neck by Dan Jordan

Farming still ranks as a leading economic driver in WNY, but those that are still in business use different methods and grow crops that are not conducive to pheasants. As large farms buy up adjoining smaller farms, they remove the hedgerows that once dominated fields and the sides of roadways. Those hedgerows once granted great protective cover and roosts for pheasants. At that same time, farmers have gone to growing corn and soybeans in great volume (crops that pheasants will not hang out in) while cutting back dramatically on hay, alfalfa, and wheat (which would create great pheasant habitat).

The rise of the predators

While the pheasant habitat dwindled and the protective hedgerows disappeared, there was an explosion in local predator populations. Cooper’s hawk, which could attack chicken-sized birds like ring-necks, have gone from uncommon to abundant. The number of red foxes and racoons grew substantially as older outdoorsmen got out of trapping and very few young outdoorsmen picked up that trade. And then there’s the coyote: An animal that was rare right through the 1980s is now pretty common — everywhere — and these large canines, which have interbred with wolves, cover a lot of territory and consume a lot of small ground dwelling animals including pheasants.

Pheasants were bred for failure

The pheasant was first introduced to New York in 1900 and by the 1940s their populations were self-sustaining. Those vast numbers at the hunting peak did not need hunt clubs or game officials to supplement their populations. But, as their habitats shrunk (and their populations as well), the DEC ramped up stocking efforts in the 1970s to compensate, keep people afield, and keep the hunting economy going. But, by doing so, they brought the worst traits to the wild.

If you are old enough to remember the Good Old Days, you will recall the large flocks of pheasants that would be found roosting in trees at nightfall. When I look at old family photos and slides from the ‘60s I am always floored by the same.

Think about your expectations of pheasants of more recent decades. Nowadays, would you ever imagine seeing a pheasant up in a tree? No, you wouldn’t. You’d probably think it was weird.

That’s because game officials bred the birds to be more ground-dwelling by choosing breeding stock that exhibited those traits and by raising them well into adulthood on game farms with overhead cover like chicken wire and drapes that kept the birds thinking their world was never any higher than 8 to 10 feet off the ground.

This was by design. The DEC did this to make pheasant harvest easier for hunters by keeping the birds at ground level and out of the tree tops.

That led to the unexpected consequence of greater harvest by predators, too. When once a fox or coyote might have looked skyward and wondered how they could catch a bird, the birds were basically served up on a platter to them as they became more grounded.

The DEC cut back on stocking

Due to all of the above factors, ring-neck pheasant populations across the state are no longer sustainable. Now, they have to be grown on a game farm and stocked to give hunters a chance.

The DEC raises 30,000 pheasants for such purposes each year at the Richard E. Reynolds game farm near Ithaca. It’s a far cry from the past when multiple farms raised them for the state. You might remember the John White game farm that was on Route 63 in the town of Alabama. That once booming game farm was decommissioned in 1999.

All of the above factors have proven to be damning to the ring-necked pheasant’s status in New York. Despite them being a non-native bird, it’s a little sad as the colorful birds added to the naturescape, allowed hunting families to bond, and put many a meal on the table and in the freezer.

Bob Confer is a WNY outdoorsman, naturalist, and founder of the Exploring the Western New York Wilds nature column. You can reach him anytime, Bob@Conferplastics.com